To celebrate our 50th anniversary, we’ve asked some of the folk who’ve helped bring Greenbelt Festival to life over the last 50 years to write a little something about their festival experiences. One blog post per month, reflecting on one decade at a time.

Last month, Jonathan Cooke wrote about the 1970s. This month it’s the turn of visual and musical artist Bev Sage to take us back to the 1980s with her roller-coaster reflections on that definitive period in the festival’s story.

Greenbelt Festival, 1980

The 1980s were wild! Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister, there were strikes and demos, yuppies were taking over with their chunky mobile phones, and Rubik’s cubes, Sylvanian Families and BMX bikes were all the rage.

70s punk had blown a hole in prog rock, and Malcolm McClaren’s post-punk film The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle was released. The 80s saw a new wave of ideas in music, art and fashion – rocking the UK – and, somehow, I was lucky enough to be right in the middle of it all.

In the late 70s – along with my husband artist and fellow pilgrim, Steve Fairnie (aka Fairnie) – we used to help Jonathan and Lindy Cooke stuff Greenbelt flyers into envelopes to post out to promote the festival. By the early 80s, in excess of 20,000 people were flocking to the festival each year. At the dawn of that decade I was a singer-songwriter in the music industry and one of the first women on the Greenbelt Board. I was in the thick of it – involved in live performances, art exhibitions, fashion shows and talks.

The bands I was a part of revelled in our Greenbelt performances across the 80s, initially performing as gospel band Fish Co (described as “lunatic, crazy, imaginative, completely over the top – a million miles down the road”) and then with future reincarnations Writz, Famous Names, The Techno Twins (electronic duo) and Casual Tease (art performance troupe).

Bev Sage & Steve Fairnie, 1981

Life, like dance music, is a series of moments – and here are just some of my Greenbelt moments…

Early 80s August bank holiday: looking out as we performed to audiences of over 20,000 twice in one day was an extraordinary experience I’ll never, ever forget – as we headlined to a rapturous Greenbelt crowd by night while still recovering from playing to Reading Festival’s heavy metal audience earlier on the same day.

We loved playing Greenbelt and we were passionate about our faith making sense in whatever arts context we found ourselves.

Fairnie was a natural showman and a brilliant MC. He was remembered for connecting with the Greenbelt crowd (whether the mainstage generator was working or not!), for his epic crowd surfing, his hot chocolate orders for the masses, his swinging from the scaffolding, his witty quips (like “settle down luvvies” and “what marvellous human beings you’ve turned out to be!”), and even introducing U2’s legendary Greenbelt performance in 1981.

Bono mentions Fairnie’s quip – “I have a vision; a television.” – in his brilliant autobiography Surrender, as Bono introduces Willie Williams to his story. We first met Willie (‘Our Willie’, as we nicknamed him) at Greenbelt when he was just 17, and he travelled with us as our lighting man extraordinaire and the editor of our fanzine, Punty. He became a wicked MC himself at later Greenbelt festivals, alongside Stewart Henderson, and, of course, he is recognised now as one of the world’s great lighting designers and show producers.

The Famous Potatoes, 1986

Also, artist Charlie Mackesy, who once leapt on stage with me to compere the mainstage at Greenbelt is now a best-selling writer and illustrator (and Oscar-winning animator) for The Boy, The Horse, The Fox and The Mole.

More iconic 80s moments for me would include Jessy Dixon in his pure white suit stunning the crowd (while festival founder James Holloway, Garth Hewitt and I leapt on stage to join his backing singer, the divine Ethel Holloway for the encore) and Bruce Cockburn‘s unforgettable and intoxicating rallying call to social justice, which inspired our festival community’s heartland.

Other amazing Greenbelt moments included performances from artists like Philip Bailey, David Grant, Steve Taylor, The Alarm, Amy Grant, London Gospel Community Choir, Fat and Frantic, Lies Damned Lies, Deacon Blue, The Proclaimers and the Violent Femmes.

Hurricane Charley in 1986 nearly tore the place apart, ripping up our fragile tent, along with many others. It was our first Greenbelt with child; our daughter Famie was a toddler and I was heavily pregnant with our son Jake. I vividly remember Deniece Williams‘s extraordinary soaring vocals and Fairnie’s promise of hot chocolate lifting the spirits of the rain-soaked crowds. Later that night, I shared a ride with Deniece who, after her blistering performance, was so gracious, even when held hostage by Famie’s violent lullaby as she screamed all the way back to the hotel – a moment I’ll never forget, while travelling alongside one of the greatest singers of the day.

Greenbelt fashion shows in the 80s were also incredibly innovative and exciting, with the awesome Rolling Magazine’s Pip Wilson‘s daughters Joy and Ann kicking off catwalk frenzies that continued throughout the decade. Motorbikes, aeroplanes, staging and a mix of brilliant designers’ clothing, models and makeup artists blazed a trail of glory. Sadness hit hard when one of our beautiful fashion show models Sarah Aicher was flying home with her fiancee on Pan Am Flight 103 when the Lockerbie bomb exploded in December 1988. She’d just written a play called Heaven and we took some heart in the hope that heavenly arms would have been flung open to welcome her home.

Back in the 80s the mainstream printed press had power: a newspaper or magazine article could make or break you. Greenbelt struggled to gain mainstream recognition while still staying relevant and true to its core church youth groups and leaders. So, founder James Holloway and I wanted to change this up and, along with others, we launched Strait in 1981 – Greenbelt’s very own quarterly answer to the NME (as we liked to think of it). Great writers like Stewart Henderson, Steve Turner and Martin Wroe (editor from 87-89) contributed excellent articles across the decade.

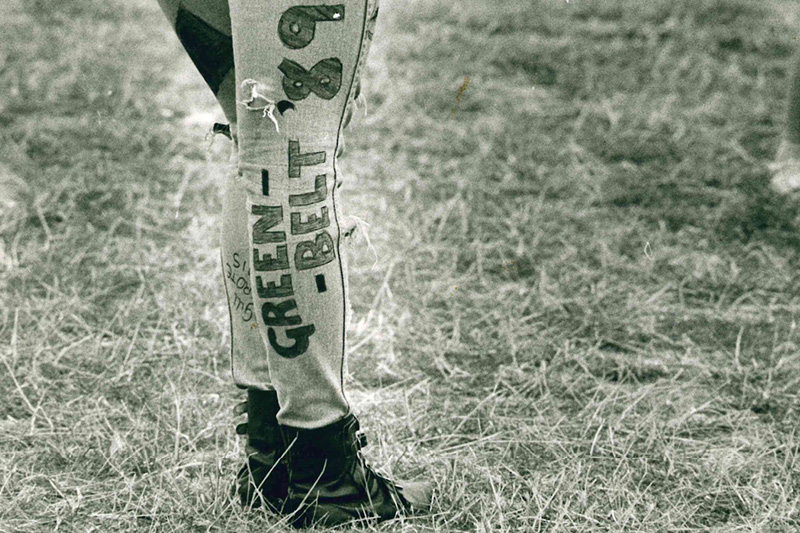

Greenbelt Festival, 1989

BBC Radio 1 provided the festival with significant national exposure, with our great friend and DJ Simon Mayo frequently broadcasting from the event. I remember a hilarious moment when Peter Powell (another Radio 1 DJ) spotted my blonde locks in the crowd and shouted out to me. I was thrilled, until I realised he thought he’d recognised Nick Beggs from Kajagoogoo (who often came to Greenbelt back then).

The festival continued to attract a diverse range of musicians, artists and speakers from different backgrounds, and I particularly loved the lineup in 1989 when Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Sweet Honey in the Rock, the Clark Sisters, Bruce Cockburn, and Charlie Peacock all graced our stages.

Always more than just a gathering for music, art, theatre, and fashion enthusiasts, Greenbelt’s wisdom and inspiration came from some of the most brilliant minds of our time. In the 80s we were led by people like (now Bishop) Graham Cray, (dear departed) John Peck, and Garth Hewitt. They, together with a host of razor-sharp thinkers, curated the festival’s seminars, workshops and panels – which grew and developed alongside the great music.

Sunday Communion, for me, has always been the heart and soul of the event, as Greenbelters share bread and wine. Just two unforgettable highlights: one, South African anti-apartheid activist Caesar Molebatsi’s powerful preaching on peace and, two, writing our hopes and prayers for the future and burying them in a massive jar in our field of dreams.

Looking back, Greenbelt’s vibrant celebration of creativity, faith, social justice and activism has connected people of all backgrounds and beliefs together. With its soulful communion, fierce discussions, and rocking performances, for 50 years now it has made a space where people can discover new ways of thinking about Christianity, the arts and social justice in their relationships, friendship and family. And while a lot has changed and developed since the 80s’ clunky and cumbersome technology, the festival is still fuelled by faith and community, something that’s never gone out of fashion.

Looking forward to the next fifty years – with today’s current strikes, demos, wars and political challenges – I’m holding close the spirit of the festival as we continue our thorny pilgrimage onwards and upwards towards a better, more just future for everyone.

Greenbelt Crowd, 1988