A guest blog from Peter Bigg – a lifelong Greenbelter, having been part of the initial Suffolk audience back in 1974 and then part of its organisation from 1977. Here’s the story of how, through Greenbelt, he got to know the work of, meet and then champion Gazan artist Malak Mattar – most recently watching proudly as she introduced Brian Eno’s ‘Together for Palestine’ gig at Wembley Arena in September 2025. (Peter had introduced Malak to Brian in the Green Room at Greenbelt 2022.)

From 1983 to 2010 I spent a good deal of my working time alongside programmers of film and video departments within contemporary art museums in the USA. Of them all, I spent most time at The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis where I became firm friends with its Curator of Film, Dean Otto.

It was Dean who responded to photographs I’d posted on my socials in 2016, when, on a trip organised by Amos Trust, I was visiting the city of Hebron in the occupied West Bank. He wondered whether I was there to attend the Gazan Film Festival. I wasn’t, but I did research it and saw extraordinary scenes of a fully-fledged festival taking place there, amidst the rubble. The most powerful image was of an incredibly long red carpet, rolled out, upon which all attendees would walk because, in the words of the organisers, “We are all stars.”

Back home, I began looking into Gazan film, documentaries and art in general. I’d long been involved with Greenbelt and was always looking for potential programming that I could suggest. My friend Esther Gibbons had also been looking and told me about a young artist called Malak Mattar. I found that Malak had a large social media following and also that some of her work had already been shown outside Gaza. Some of it had been exhibited in The Palestinian Museum in Bristol, and they still had three canvases – all of which were for sale. I bought all three and mounted them onto gallery frames. I still have them.

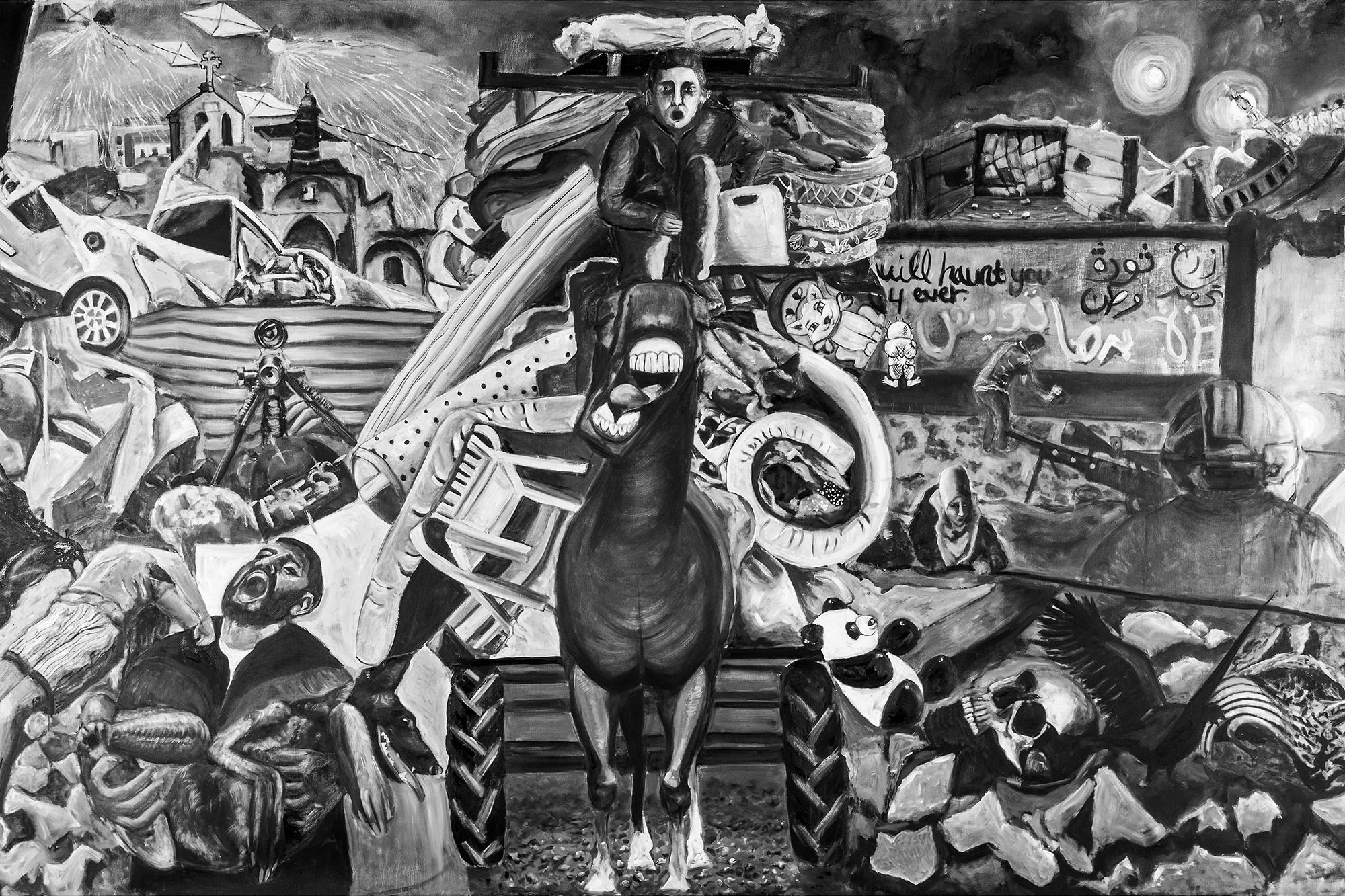

THAWRA

I sent photographs of them to Greenbelt’s creative director, Paul Northup who loved them and we began a process whereby Malak would be invited to exhibit her work at the 2018 festival at Boughton House. It was at least a year away, and although the logistics of leaving Gaza were troubling at the time, they weren’t insurmountable. As the time drew closer, I asked Baroness Sayeeda Warsi (who had spoken at the 2017 festival) if she would be willing to write a letter to accompany Malak’s visa application. She asked me to write the letter of support, which she would willingly sign as a Privy Councillor.

Meanwhile, in Gaza, Malak was finishing her schooling and her results were expected to be extraordinary. The Palestinian Authority can grant their top five students permission to study abroad and Malak, with the highest marks in Gaza and the second highest in the whole of Palestine, was expected to receive this permission. She had a tentative offer to study in Istanbul but the permission never materialised – probably because she was in Gaza, over which the Palestinian Authority has little influence. I thought this was a gross miscarriage of justice and was determined to help.

Back in 2016, my visit to Palestine had included two hours of a Sunday afternoon spent with Dr Husam Zomlot, the then Chief Strategic Advisor to President Mahmoud Abbas. He was a wonderful speaker, full of knowledge and passion. Remembering him, I emailed him at the Presidential Palace in Ramallah, outlining Malak’s plight. Despite Sayeed Warsi’s letter of support, Malak’s visa application to attend her own exhibition at Greenbelt 2018 was refused.(2)

But I had all the canvases for the exhibition and we determined to continue with it, even without Malak’s appearance. That year, eighteen works were exhibited in The Tapestry Room within Boughton House, and some were sold. During the festival we were even able to Skype Malak onto the screen in the venue. Many festivalgoers were in tears as they spoke with her after viewing her work and knowing her story.

Midway through the weekend, Malak shared an image with us. It was a self-portrait of a sad looking girl caressing a picture of Sufis dancing. She had painted it that day and called it simply ‘Greenbelt.’ I bought it before the paint had even dried. After the festival, I had prints made and travelled to Istanbul to get them signed and numbered.

When, eventually, Malak was able to begin her study in Turkey, she needed to earn money from her art to help her student life in Istanbul. I was asked to become a sort of ‘manager’ for her work. I accepted, not knowing what it might mean, not knowing how long it might last and, declining only Malak’s generous offer of a percentage of sales, I set about organising images so that they could be sold through an Etsy shop. Malak’s social media was crucial in driving early sales and I’d found a printer who could make incredible giclee prints. The Etsy shop began with only 5* reviews and has maintained it half a decade later.

The first advice of any sale that an Etsy shop manager receives is an email. One morning in the summer of 2021, my inbox was full of these messages. They were all for the same image “You and I”, a work I owned. For a few days, I was shipping dozens of these prints every day. It was a complete surprise to Malak but she remembered an interview with a Middle Eastern magazine and wondered whether I’d ever heard of something called GQ?! They had printed her interview in their June issue and crucially had also used its image on the cover!

You and I

During 2021 we began to think about getting Malak and her work to Greenbelt in 2022, the first year the festival made a return after COVID. Although eager, Malak was concerned that her previous visa refusal could compromise any further application. Compounding this was her recalling the reason for the refusal – that she wasn’t considered to be a student (because she hadn’t yet started her studies in Istanbul). By 2022, her studies had finished in Istanbul and so the same argument could have been made by the Home Office.

Malak put in her application in good time and heard nothing for a long while – until it was refused again. The despondency was palpable. I had already written to my local MP, one Priti Patel, asking that, like Sayeeda three years previously, she might consider writing a letter of support to include with Malak’s visa application. She replied that the application process had been revised and that any additional information, unless requested, was to be ignored. I wrote back to suggest that a mistake had been made. What made this letter different was that Priti Patel was now Home Secretary – with ultimate responsibility for who comes into the country.

The next day, an excited Malak called me. She was in a taxi, on her way to the British Embassy in Istanbul. She had been called and asked to take her passport. A few hours later, my screen lit up with a picture of a multiple entry visa. I wrote to Priti thanking her and she sent me a copy of a note she’d received from Istanbul. It was obvious that she’d made a phone call. Late one night at Stansted airport, and only a day before the festival two very happy people re-connected. Many people at Greenbelt had heard about the visa refusal, less that it had been reversed. The show that year was a triumph and Malak’s presence was magical.

After one of the Amos Trust curated session showings in 2022, when festivalgoers had the chance to chat with Malak, I noticed one person taking up a lot of this short time and, anxious that other people were not being seen and that perhaps Malak was in an uncomfortable situation, I edged myself closer. Malak motioned that she was OK and introduced me to this man by the name of Jonathan. She had become intrigued by his questioning which wasn’t about Gaza or any life experiences but more technical queries about her work. She asked whether he was an artist. His response was one I shall never forget. “I am. My name is Jonathan Kearney, and I am the director of the Fine Art degree course at Central Saint Martins and I would love to teach you.” He wanted to make clear that the timing should be at Malak’s discretion and that she shouldn’t feel pressurised, even though others listening to the conversation including ex-festival staff Jacqui Christian and Su Plater were also thinking of ways to deploy their professional expertise to Malak’s benefit.

Malak had applied to Arts Council England to be granted a Global Talent Visa. It was granted with a citation that she was deemed to be ‘an extraordinary talent.’ She was accepted to Central Saint Martins to commence an MA in Fine Art, beginning in October 2023 and had secured a one-year scholarship from The Said Foundation whose Amal project had brought an Islamic art to the programme of Greenbelt in 2019. She’d found accommodation in North London, and I arranged to meet her for lunch on the day after she arrived. It was the 7th October and the news streams were filling with an important development in Gaza. Neither of us realised the significance of this until later in the day.

Gaza is a Phoenix

Continuing sales of prints through Etsy allowed Malak to live in central London throughout her course and, by the summer of 2025, we had reached sales of two thousand prints.

In the summer of 2025 Malak graduated with distinction (MA in Fine Art) and became the first Palestinian to have an exhibition at Central Saint Martins. The private view was attended by over 300 people, including Husam Zumlot who spoke to rapturous applause. Malak’s family, recently granted permission to live in the UK, were also there to witness her success.

Jonathan Kearney hadn’t been the only artist Malak had met at the 2022 festival. Back in the 1970s when working with ‘After The Fire’, I’d attended a church in Colchester and was friends with a girl by the name of Bee who later married Brian Eno’s brother, Roger. I introduced myself to Brian with this story at what was his first Greenbelt experience, then introduced him to Malak. In September 2025, her work was shown in collaboration with the British artist Es Devlin, as the digital backdrop to Brian Eno’s star-studded ‘Together for Palestine’ fundraiser at Wembley Arena. As the event’s artistic director she also introduced the whole event.

—————————

Notes

- I didn’t receive an answer immediately, and Husam was soon moved to be the Palestine envoy to Washington. It was only in 2025, when I re-connected with Husam in London (where he is now the Palestinian ambassador to the UK), that I discovered Malak’s travel had been facilitated by him.

- Greenbelt asked its own local MP for assistance in mounting an appeal but he, Keir Starmer, was unable to assist. The reason given for the visa refusal was that although Malak was technically a student with a place at a Turkish university, she was a few weeks away from commencing her studies and it was thought she didn’t have enough of a reason to leave the UK after her visit.